| [fəˈnɛɾəks] |

What makes one consonant different from another?

Producing a consonant involves making the vocal tract narrower at some location than it usually is. We call this narrowing a constriction. Which consonant you're pronouncing depends on where in the vocal tract the constriction is and how narrow it is. It also depends on a few other things, such as whether the vocal folds are vibrating and whether air is flowing through the nose.

We classify consonants along three major dimensions:

The place of articulation dimension specifies where in the vocal tract the constriction is. The voicing parameter specifies whether the vocal folds are vibrating. The manner of articulation dimesion is essentially everything else: how narrow the constriction is, whether air is flowing through the nose, and whether the tongue is dropped down on one side.

For example, for the sound [d]:

The vocal folds may be held against each other at just the right tension so that the air flowing past them from the lungs will cause them to vibrate against each other. We call this process voicing. Sounds which are made with vocal fold vibration are said to be voiced. Sounds made without vocal fold vibration are said to be voiceless.

There are several pairs of sounds in English which differ only in voicing -- that is, the two sounds have identical places and manners of articulation, but one has vocal fold vibration and the other doesn't. The [θ] of thigh and the [ð] of thy are one such pair. The others are:

| voiceless | voiced |

| [p] | [b] |

| [t] | [d] |

| [k] | [ɡ] |

| [f] | [v] |

| [θ] | [ð] |

| [s] | [z] |

| [ʃ] | [ʒ] |

| [tʃ] | [dʒ] |

The other sounds of English do not come in voiced/voiceless pairs. [h] is voicess, and has no voiced counterpart. The other English consonants are all voiced: [ɹ], [l], [w], [j], [m], [n], and [ŋ]. This does not mean that it is physically impossible to say a sound that is exactly like, for example, an [n] except without vocal fold vibration. It is simply that English has chosen not to use such sounds in its set of distinctive sounds. (It is possible even in English for one of these sounds to become voiceless under the influence of its neighbours, but this will never change the meaning of the word.)

In the stop [t], the tongue tip touches the alveolar ridge and cuts off the airflow. In [s], the tongue tip approaches the alveolar ridge but doesn't quite touch it. There is still enough of an opening for airflow to continue, but the opening is narrow enough that it causes the escaping air to become turbulent (hence the hissing sound of the [s]). In a fricative consonant, the articulators involved in the constriction approach get close enough to each other to create a turbluent airstream. The fricatives of English are [f], [v], [θ], [ð], [s], [z], [ʃ], and [ʒ].

In an approximant, the articulators involved in the constriction are further apart still than they are for a fricative. The articulators are still closer to each other than when the vocal tract is in its neutral position, but they are not even close enough to cause the air passing between them to become turbulent. The approximants of English are [w], [j], [ɹ], and [l].

An affricate is a single sound composed of a stop portion and a fricative portion. In English [tʃ], the airflow is first interuppted by a stop which is very similar to [t] (though made a bit further back). But instead of finishing the articulation quickly and moving directly into the next sound, the tongue pulls away from the stop slowly, so that there is a period of time immediately after the stop where the constriction is narrow enough to cause a turbulent airstream. In [tʃ], the period of turbulent airstream following the stop portion is the same as the fricative [ʃ]. English [dʒ] is an affricate like [tʃ], but voiced.

Pay attention to what you are doing with your tongue when you say the first consonant of [lif] leaf. Your tongue tip is touching your alveolar ridge (or perhaps your upper teeth), but this doesn't make [l] a stop. Air is still flowing during an [l] because the side of your tongue has dropped down and left an opening. (Some people drop down the right side of their tongue during an [l]; others drop down the left; a few drop down both sides.) Sounds which involve airflow around the side of the tongue are called laterals. Sounds which are not lateral are called central.

[l] is the only lateral in English. The other sounds of Englihs, like most of the sounds of the world's languages, are central.

More specifically, [l] is a lateral

The place of articulation (or POA) of a consonant specifies where in the vocal tract the narrowing occurs. From front to back, the POAs that English uses are:

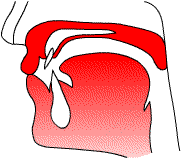

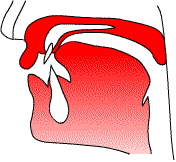

In a bilabial consonant, the lower and upper lips approach or touch each other. English [p], [b], and [m] are bilabial stops.

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during a typical [p] or [b]. (An [m] would look the same, but with the velum lowered to let out through the nasal passages.)

The sound [w] involves two constrictions of the vocal tract made simultaneously. One of them is lip rounding, which you can think of as a bilabial approximant.

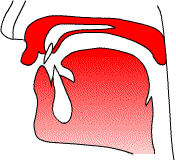

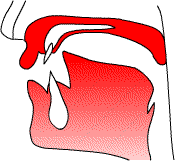

In a labiodental consonant, the lower lip approaches or touches the upper teeth. English [f] and [v] are bilabial fricatives.

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during a typical [f] or [v].

In a dental consonant, the tip or blade of the tongue approaches or touches the upper teeth. English [θ] and [ð] are dental fricatives. There are actually a couple of different ways of forming these sounds:

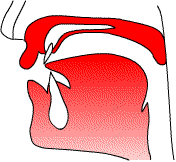

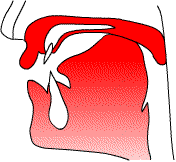

In an alveolar consonant, the tongue tip (or less often the tongue blade) approaches or touches the alveolar ridge, the ridge immediately behind the upper teeth. The English stops [t], [d], and [n] are formed by completely blocking the airflow at this place of articulation. The fricatives [s] and [z] are also at this place of articulation, as is the lateral approximant [l].

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during plosive [t] or [d].

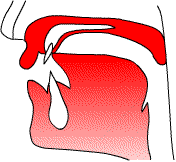

In a postalveolar consonant, the constriction is made immediately behind the alveolar ridge. The constriction can be made with either the tip or the blade of the tongue. The English fricatives [ʃ] and [ʒ] are made at this POA, as are the corresponding affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ].

The diagram to the right shows the state of the vocal tract during the first half (the stop half) of an affricate [tʃ] or [dʒ].

In a retroflex consonant, the tongue tip is curled backward in the mouth. English [ɹ] is a retroflex approximant -- the tongue tip is curled up toward the postalveolar region (the area immediately behind the alveolar ridge).

The diagram to the right shows a typical English retroflex [ɹ].

Both the sounds we've called "postalveolar" and the sounds we've called "retroflex" involve the region behind the alveolar ridge. In fact, at least for English, you can think of retroflexes as being a sub-type of postalveolars, specifically, the type of postalveolars that you make by curling your tongue tip backward.

(In fact, the retroflexes and other postalveolars sound so similar that you can usually use either one in English without any noticeable effect on your accent. A substantial minority North American English speakers don't use a retroflex [ɹ], but rather a "bunched" R -- sort of like a tongue-blade [ʒ] with an even wider opening. Similarly, a few people use a curled-up tongue tip rather than their tongue blades in making [ʃ] and [ʒ].)

In a palatal consonant, the body of the tongue approaches or touches the hard palate. English [j] is a palatal approximant -- the tongue body approaches the hard palate, but closely enough to create turbulence in the airstream.

In a velar consonant, the body of the tongue approaches or touches the soft palate, or velum. English [k], [ɡ], and [ŋ] are stops made at this POA. The [x] sound made at the end of the German name Bach or the Scottish word loch is the voiceless fricative made at the velar POA.

The diagram to the right shows a typical [k] or [ɡ] -- though where exactly on the velum the tongue body hits will vary a lot depending on the surrounding vowels.

As we have seen, one of the two constrictions that form a [w] is a bilabial approximant. The other is a velar approximant: the tongue body approaches the soft palate, but does not get even as close as it does in an [x].

The glottis is the opening between the vocal folds. In an [h], this opening is narrow enough to create some turbulence in the airstream flowing past the vocal folds. For this reason, [h] is often classified as a glottal fricative.

| [p] | voiceless | bilabial | plosive |

| [b] | voiced | bilabial | plosive |

| [t] | voiceless | alveolar | plosive |

| [d] | voiced | alveolar | plosive |

| [k] | voiceless | velar | plosive |

| [ɡ] | voiced | velar | plosive |

| [tʃ] | voiceless | postalveolar | affricate |

| [dʒ] | voiced | postalveolar | affricate |

| [m] | voiced | bilabial | nasal |

| [n] | voiced | alveolar | nasal |

| [ŋ] | voiced | velar | nasal |

| [f] | voiceless | labiodental | fricative |

| [v] | voiced | labiodental | fricative |

| [θ] | voiceless | dental | fricative |

| [ð] | voiced | dental | fricative |

| [s] | voiceless | alveolar | fricative |

| [z] | voiced | alveolar | fricative |

| [ʃ] | voiceless | postalveolar | fricative |

| [ʒ] | voiced | postalveolar | fricative |

| [ɹ] | voiced | retroflex | approximant |

| [j] | voiced | palatal | approximant |

| [w] | voiced | labial + velar | approximant |

| [l] | voiced | alveolar | lateral approximant |

| [h] | voiceless | glottal | fricative |

The following is the chart for English consonants:

| bilabial | labiodental | dental | alveolar | postalveolar | retroflex | palatal | velar | glottal | ||||||||||

| plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||||||

| nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||||||

| fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||||||

| approximant | (w) |

ɹ | j | (w) | ||||||||||||||

| lateral approximant | l | |||||||||||||||||

| affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||||||