Bob Travica

Indiana University

Library 011

Bloomington, IN 47405

812/855-3259

btravica@indiana.edu

ABSTRACT

Can information-communication technology enable new organizational designs, such as the

networked organization and the adhocracy? An exploratory study into the accounting industry

was undertaken in order to improve our understanding of this problem. On the basis of the

literature of new designs a non-traditional organization model was developed in which

information-communication technology was juxtaposed to a number of structural and cultural

dimensions. The model was tested on a set of offices in the accounting industry and corroborated

for the most part.

KEYWORDS

Information technology, communication technology, CSCW, collaboration, organizational design,

organic organization, technology impacts

1. Introduction

The problem of the relationship between information-communication technology and new

organizational designs has attracted a significant attention of researchers in recent years.

Information-communication technology (ICT), such as electronic mail (e-mail), electronic bulletin

boards, and groupware, have been studied from the point of their impacts on various

organizational dimensions and new organizational designs. A host of new organizational designs

that in various degrees put the stress on ICT have been proposed. Examples include the

adhocracy [30], the information/knowledge-based [16], and shamrock [19] and the network

organization [44]. A common denominator of the models is a criticism of the traditional

hierarchical or command-and-control organization's inefficiency and ineffectiveness in this time of

tremendous changes in organizational environments. The denial of the traditional organization is

complemented by conceptualizations of alternatives to its characteristics, such as less of hierarchy,

centralization and formalization, and more of teamwork and cooperation/collaboration.

Although roots of the modern thinking about the non-traditional organization date decades back [9] our understanding of why and how this organization comes to be is still partial. Some forces that take part in its creation are better understood than others. Specifically, a consensus exists regarding the impacts of organizational environment, while the role of organization strategy is subject to controversy; for example, Mintzberg and McHugh [31] demonstrated that strategy may decisively shape a new organization, whereas Baker's [4] study showed only limited impacts of strategy. However, the least understood remains the role of ICT in new organizational designs. Although normative research is not lacking [e.g., 8, 29, 32, 33, 46] empirical studies are still in short supply [e.g., 19, 35, 37, 42]. An exploratory study into the relationship between ICT and a new organizational design was undertaken in order to improve our understanding of the link between ICT and new designs. A design labelled with the 'non-traditional organization' was developed and tested on a sample of twelve local offices from five biggest accounting firms.

2. Previous Research

ICT and new designs of organizing have been investigated in various disciplines, separately more

often than in relation to each other. The accounting industry has not been viewed as a potential

domain of new designs. The study linked ICT, new designs and accounting industry on the basis

of literature briefly discussed below.

2.1 Information-Communication Technology

ICT was conceptualized by a number of researchers as electronic machines, devices, and their

applications that have both computing and communication capabilities. For example, Child [12]

defined ICT as technologies and applications which combine the data-processing and storage

powers of computers with the distance-transmission capabilities of telecommunications. Similarly,

Huber [21] defined 'advanced IT' as devices (a) that transmit, manipulate, analyze, or exploit

information, and (b) in which a digital computer processes information integral to the user's

communication or decision task. Exemplars of ICT are electronic mail (e-mail), conferencing

technologies, electronic bulletin boards, file transfer, collaboration technology (e.g., group

support systems), shared electronic databases, electronic data interchange, the fax, voice mail and

the telephone. The last three, although often being classified exclusively as communication

technologies, are enlisted here because they (1) are pervasive, and (2)

are increasingly acquiring

computing capabilities (e.g., v-mail systems rest on the computer, the fax can be

computer-mounted, while the telephone is getting part of integrated computer-telephone

systems).

The relationship between ICT and organization structure dimensions was investigated by Whisler [60] who found that a reduction of hierarchy layers was associated with the use of computers in the insurance industry. Similarly, Pool [39] argued that the telephone led to aberrations from hierarchical patterns in the old steel industry because it made possible for workmen to access executives. Next, smaller formalization was found to be related to the use of computer systems in manufacturing firms [38] and in various industries [63]. Centralization was also found to relate to ICT, although in a diversified fashion. The link between ICT and decentralization at the operational level was discovered in railroad management [14] and in city departments of human resources [23]. Overall decentralization was related to ICT in manufacturing [38], small newspaper organizations [10] and in a hospital [7]. However, it was also discovered that ICT related to increased centralization at the executive level in the insurance industry Whisler [6], large newspaper organizations [10], and railroad management [14]. Finally, ICT-related spatial dispersion was discovered in organizations of scientists [20, 24] and a software vendor [35].

Organizational culture refers to patterns of shared values and behaviors of organization members. Of interest for this review are those values and behaviors that have been researched in relation to ICT. Several studies in laboratory and organizational contexts found that e-mail and other ICT, due to the lack of social cues they imposed, could lead to relatively uninhibited behavior, social equalization, decision shifts and creation of new ideas [52, 49]. The relatively uninhibited behavior was sometimes interpreted as an undesirable aberration from social norms [25], while at other times it was deemed stimulating to organizational innovation [52, 53]. Inversely, the occurrence of uninhibited behavior was attributed to personal and group characteristics rather than to ICT itself [51]. Other findings were that ICT could help people to avoid conformism [50], express feelings more honestly [see 61] and create a community of spatially dispersed organization members when social communication bursts out in a bureaucratic organization [17] or when scientists utilize ICT on a regular basis [24]. In addition, significant cooperation in knowledge sharing was discovered in ICT-rich organizations [15,35]. Moreover, changes in accountability patterns were found among ICT users [18]. Finally, many studies found that communication via ICT is likely to cross spatial and department boundaries [20, 24, 35, 48, 53].

2.2 New Organizational Designs

Burns and Stalker's [9] 'organic organization' is a historical blueprint for new organizational

designs. Authors derived the organic design from their empirical studies of successful electronics

firms. The design is characterized by flexible tasks, a network-like pattern of control, authority

and communication, communicating of information and advice rather than instructions and

decisions, and commitment to a 'technological ethos' rather than loyalty and obedience.

Mintzberg's [30] adhocracy is another influential design. It is characterized by low formalization,

flatter hierarchy, vague roles, the reliance on team work and employee cooperation, and intensive

communication. Evidence on the adhocracy accrued from several studies, which also expanded

the model [3, 31, 35]. For example, Olson & Bly [35] proposed that the adhocracy required a

strong ICT support. The third design of interest is the networked organization. Rockart and Short

[44] propose the networked organization design at the nexus of which are informal human

networks enabled by ICT networks. These socio-technical networks can foster redesigning the

division of labor, and the development of a new culture characterized by sharing of goals,

expertise, decision making, recognition and reward, responsibility, accountability and trust (one of

critical dimensions). Morgan [32, 33] proposes the loosely-coupled organic network, which rests

on a founding/driving team and subcontracting. Baker [4] defines the networked organization as

that which is highly integrated across vertical, horizontal and geographical boundaries, and finds

that a small real estate firm he has studied fits his concept to a moderate extent.

2.3 Accounting Industry

In the search of new organizational designs one can follow leads from literature. For example,

rational choice/strategy of making a different organization [4, 31], turbulent environments [9],

industries in flux such as software engineering [19], organizations that rest on intensive social

networking [40, 41], and professional and high technology organization [30]. Another approach is

to draw a preliminary model of a new design, and then contrast it against organizations across

industries in order to identify a study population. The study reported here chose the latter

approach because one of its goals was to synthesize unsystematized literature of new designs into

a new model of the non-traditional organization.

A dozen of small organizations from manufacturing, insurance, engineering, data services, and accounting were investigated in terms of their hierarchy, departmentation, span of control, formalization, team work, management promotion policies, pace of organizational change, and the extent of ICT usage, its perceived importance, kinds of ICT uses and perceived effects of the uses. The extent of team work and ICT profile (inventory, perceived importance and effects, and kinds of uses)--both important in the literature of new designs--showed (unexpectedly!) that the accounting industry was a candidate for the full-fledged study rather than other industries.

The accounting industry houses three major practices - account auditing, tax preparation and planning, and consulting. The first one is the oldest and was responsible for starting the modern accounting industry in the U.S. in the l9th century. The tax business was a later entrant, which made accountants compete with law firms. The consulting practice started after WWII and have progressed from 'management advisory services' towards information systems consulting. In the provision of consulting services accountants compete with several industries. [54, 55] Interestingly, the industry has developed properties which mirror ideas from new organizational designs, such as, lower hierarchy and centralization, team work, client orientation, and advanced applications of information practices and technology. A tension between the professional and bureaucratic organization seems to constitute much of the industry's organizational dynamics[2]. One line of divison runs through practices, with consulting being more organically organized than auditing [58]. Stevens [55] argued that an increasing emphasis on consulting not only as practice but also as an orientation was underway. Also, Quinn [42] argued that one of biggest accounting firms resembled a 'spider web' organization with its flat structure, independent units, firm-wide communication and databases systems for sharing information and knowledge, teamwork, and the sharing of responsibilities.

It should be noted that the accounting industry provides a favorable context in which organization size can be controlled, while variation of the ICT usage across local offices is secured. Specifically, the basic organizing form in the industry, a local office, may not vary size-wise while it can have a considerable discretion in planning and conducting operations, deployment of ICT, marketing, and incentive systems and other management systems. In effect, a local office can be treated as a semi-independent entity that shares the size attribute with offices from other firms, while differing on the ICT usage from offices of the same firm.

3. Methodology

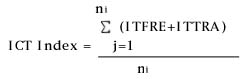

The study was to test a model of the non-traditional organization depicted in Figure 1. ICT was

conceptualized as the amount of usage of the telephone, the fax, voice mail, e-mail, shared

electronic databases, file transfer and electronic bulletin boards. Two measures were used for

assessing the ICT usage: (1) ITTRA - the number of transactions (any act of sending or receiving

data via the ICT mentioned) in a typical day; and (2) ITFRE - the frequency of using the ICT

mentioned. (For complete variable and measure definitions and sources please see Appendix.)

Non-traditional dimensions were based on the literature discussed above. Formalization,

centralization and hierarchy were expected to be lower and/or relate negatively to ICT (the same

intentions could have expressed by using a 'de-' prefix--decentralization, etc.).

In accordance with the study problem, the main relationship in the model is that between ICT and other dimensions postulated as dependent ones. It is captured in the following research question: Does ICT enable the non-traditional organization; if yes, to what extent? The enabling concept refers to Orlikowski's [36] concept whose implication is that ICT is just one of forces capable of creating the non-traditional organization. As the model shows, multiple forces can be at work that can influence both dependent dimensions and each other.

Data were collected via surveying professionals (independent and dependent variables) and interviewing partners (control variables) in 12 local offices from big accounting firms on the East Coast and in the Mid West. In order to obtain information for answering the research question, individual responses were aggregated onto the office level by the means of two new measures. One was the index of information-communication technology (ICT Index) that was computed as:

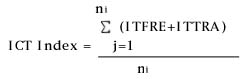

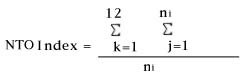

where j signifies a respondent, i signifies a local office, and ni is the number of respondents in a local office. The other aggregate measure was the non-traditional organization index (NTO Index) that was computed as:

where k signifies a dependent measure and Y is a dependent measure. After the indexes were computed, correlation analysis (zero-order) was run to obtain the product-moment correlation coefficient for the indexes.

4. Findings

The main finding pertaining to the research question is that the relationship between the ICT

Index and the NTO Index is r=0.62 p<0.03, the 38% of variance explained. (The Spearman rho

for indexes is 0.65, p<0.02.) Put another way: The higher the IT usage in an office, the more

developed the office's non-traditional characteristics. Table 1 depicts the distribution and

descriptive statistics of the indexes.

Table 1 The Distribution and Descriptive Statistics

| Office | NTO | ICT | Office | NTO | ICT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Index | Index | Index | ||

| Office A | 59.89 | 59.44 | Office G | 59.82 | 58.49 |

| Office B | 60.91 | 58.74 | Office H | 60.21 | 58.78 |

| Office C | 60.20 | 58.97 | Office I | 59.02 | 58.72 |

| Office D | 60.16 | 58.04 | Office J | 61.49 | 59.33 |

| Office E | 58.93 | 58.70 | Office K | 61.26 | 60.24 |

| Office F | 58.54 | 57.95 | Office L | 59.90 | 58.67 |

| N | Mean | S.D. | Max | Min | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTO Index | 12 | 58.84 | 0.62 | 60.24 | 57.95 | 2.29 |

| ICT Index | 12 | 60.02 | 0.91 | 61.49 | 58.54 | 2.95 |

Table 2 depicts descriptive statistics for dependent varibales across 12 offices (all estimates based on a 0-4 point scale, 0=minimum, 4=maximum), and provide a picture of a 'typical office' studied.

Table 2 'Typical Office' Studied

_________________________________________________

| Mean | S.D | Hierarchy | 130 | 2.04 | 0.63 | Formalization | 131 | 2.81 | 0.62 | Centralization | 130 | 2.09 | 0.62 | Latent Spatial Dispersion | 131 | 2.46 | 0.72 | Knowledge Giving | 131 | 3.41 | 0.49 | Knowledge Getting | 131 | 2.66 | 0.72 | Accountability Sharing | 123 | 3.32 | 0.56 | Trust Sharing | 131 | 2.30 | 0.21 | Outbound Communication | 130 | 1.80 | 0.96 | Role Ambiguity | 131 | 1.16 | 0.60 | |

|---|

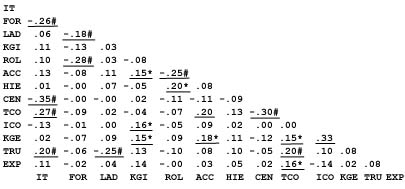

Figure 2 depicts correlations of all variables. It suggest that the variable of ICT usage correlates with formalization, centralization (both correlations are inverse), outbound communication, and the sharing of trust. In addition, important variables appear to be outbound communication and accountability sharing, because they have multiple links to other variables. Most of the relationships were anticipated; however, some expected ones were not found.

5. Discussion

The finding on the positive and strong correlation between two index measures suggests that ICT

enables the non-traditional organization to a significant extent. Other forces that can make

impact--size, environment and strategy--did not vary significantly across offices studied. The ICT

enabling instantiates in its relationships with two structural and two cultural dimensions.

Specifically, ICT relates negatively to formalization and centralization, which confirms findings

from previous research [6, 38 and 10, 14, 23, 38, respectively]. The formalization finding may be

understood so that heavier ICT users find themselves more in novel tasks/situations that are not

prescribed by rules and regulations. The centralization finding may imply that heavier ICT users

feel like they have more discretion in their work because superiors have smaller say or influence in

professionals' work.

The study, however, did not confirm the negative relating of ICT and hierarchy that was reported by [60] and hypothesized by several authors [16, 21, 39, 62]. One way of explaining the finding is by putting the previous research in the historical perspective. If so, then the hypotheses cited can be seen as still new. On the hand, Whisler's study reflected the time of 1960's when the national cultural environment challenged hierarchy while computers were simultaneously taking over in business organizations. Computer thus could support/magnify the dehierarhization trend, and so conditions for ICT enabling were in place. Today, however, this impact of environment may be missing today. Another explanation for the hierarchy finding can be sought in peculiarities of the industry. Specifically, the average hierarchy in the sample studied is four levels management, which is in accord with previous accounting research [2]. Also, the hierarchy found is equivalent to hierarchy in some small organizations [38] or is smaller than hierarchy usually reported in structure research. However, the range of hierarchy scores is six (minimum=1, maximum=7), and they vary randomly from one respondent to another. This indetermination of perceived hierarchy might reflect the actual condition of the accounting professional that he is affected more by 'enacting hierarchy', the one that works upon him, than by the official one which practically is invariant.

The relationship between ICT and outbound communication, along with its implication that the former supports the latter, confirms findings from previous studies, although they investigated different populations [cf. 20, 24, 35]. The link between ICT and trust is a new finding and can be understood so that the ICT mediation in professionals' work does not diminish trust, which is important for collaborative culture to sustain.

Outbound communication has multiple correlates, thus appearing as a hub in the variable set. Interpreting the correlates, it seems that in more centralized contexts the room for team members communication with outsiders shrinks because they can/need to initiate less of interacting on their own. In addition, outbound communication may open up a team to its environment. Since a team of auditors, tax specialists or consultants is typically focused on its project, main communication develops among team members than with outsiders. External communicating bears costs that make it acceptable only when it satisfies a precious, work-related need. In effect, a team acts as a self-sufficient and a self-contained unit. This may lead to the team's winding up as a closed system, which could endanger collaborative culture. Trans-boundary communication in this context can serve as the vehicle for preventing these undesirable outcomes. It balances forces that may act in opposite directions--the centripetal force (team-based accountability) and the centrifugal force (getting knowledge from outsiders).

Findings also indicate that accountability sharing with its multiple correlates is another important variable. It was found that the burden of accountability was collaboratively carried by team members in situations of defining the scope of work, controlling team budget and organizing teamwork. As one respondent put it conspicuously: "Each member duties were delegated by the manager. However, after discussing what needed to be done, the team reassigned duties. The manager asked why. We explained and he agreed." The statement also tells something about exercising of control horizontally and upward.

Finally, the discovered relationships between variables of knowledge giving, knowledge getting and accountability sharing corroborate propositions from literature [see 44], and add information to the portrait of the typical professional studied: He is a dynamic professional that uses ICT more intensively, has more of discretion in his work, actively exchanges knowledge with colleagues, collaborates with team mates in carrying the burden of accountability, and is more trustful.

In overall, the study's findings suggest that the model of the non-traditional organization works at the sample studied to a satisfactory extent. However, a denser pattern of ICT and other correlates that the one found could be expected. The study employed a number of new measures that need revision; also, the previously tested measures of ICT usage failed meet expectations (the r between them is only 0.47, p<.0001). In addition, larger and more heterogenous samples need to be investigated in order to validate further the model.

APPENDIX

Variables and Measures

Variables making the research model along with appropriate measures are

defined below.

ICT Usage: The extent to which ICT is used [20]. Measures: ICT Usage by frequency

(ICTFRE): The frequency of usage within time periods [13].

ICT Usage by the transactions typically (ICTTRA): The number of transactions in a typical day

[1].

Formalization: The extent to which rules, procedures, instructions and communcations

are written [34]. Measure: same source.

Centralization: The extent to which control is concentrated [56]. Measure: control graph

modified [28].

Hierarchy: The number of management levels [59]. Measure: new two-item

question.

Knowldege Getting: The extent to which a professional gets knowledge from

colleagues [44]. Measure: new two-item scale.

Knowledge Giving: The extent to which a professional makes his

knowledge available to colleagues [44]. Measure: new three-item scale.

Trust Sharing: The extent of a team member's expectancy that statements of his

co-workers can be relied upon [45]. Measure: MacDonald and colleagues' [27 ] modification of

Rotter's [45] scale; slightly modified.

Accountability Sharing: The extent of a team member's condition of being ready to

justify his team's decisions to superiors [57]. Measure: new four-tem scale.

Outbound Communication: The extent to which a team member communicates across

his team's boundaries [20, 24]. Measure: new three-item scale.

Role Ambiguity: The extent to which necessary information is

lacking to an organizational

position [22]. Measure: The intensity of one's perception that necessary information is available

[43].

Size: The scale of an organization's operations. Measure: new one item question.

Environment: The extent to which forces out of organizational boundries affect an

organization [26]. Measure: a partner's assessment of local the office's clients and competitors;

new multi-item questions.

Strategy: The extent to which an organization's plans of

long-term goals affect the

organization [11]. Measure: a partner's descriptions of the local

office's business and ICT plans;

new multi-item closed- and open-ended questions.

Figure 2 Correlations between All Variables

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Note: #=significant at the .05 or better level; *=significant

at a better than .1 level. correlations

are those with p values equal or smaller than .10. Labels: IT=IT Usage, FOR=Formalization,

LAD=Latent Spatial Dispersion, KGI=Knowledge Giving, ROL=Role Ambiguity,

ACC=Accountability Sharing, HIE=Hierarchy, CEN=Centralization, TCO=Trans-Boundary

Communication, ICO=Information Gathering Collaboration, KGE=Knowledge Getting,

TRU=Trust Sharing, and EXP=Expert Power.

REFERENCES

2. Aranya, Nissim, and Kenneth R. Ferris (1984), "A Reeximination of Accountants'

Organizational- Professional Conflict" The Accounting Review, 59(10), 1-15.

3. Bailey, Arlyne, and Eric H. Nielsen (1992), "Creating a

Bureau-Adhocracy: Integrating

Standardized and Innovative Services in a Professional Work Group," Human Relations, 45, 7,

687-7.

4. Baker, Wayne E. (1922), "The Network Organization in Theory and

Practice," in Nohria,

Nitin, and Robert E. Eccles (1992), pp. 397-429. Barley, Stephen R. (1990), "The Alignment

of Technology and Structure Through Roles and Networks", in Administrative Science

Quarterly, 35 (1990): 61-103.

5. Benjamin, Robert, and Jon Blunt (1993), "The Information

Technology Function in the

Year 2000: A Descriptive Vision." Sloan Management Review. In Print.

6. Baker, Wayne E. (1992), "The Network Organization in Theory and

Practice," in Nohria,

Nitin, and Robert E. Eccles (1992), pp. 397-429.

7. Barley, Stephen R. (1990), "The Alignment of Technology and

Structure Through Roles and Networks", in Administrative Science

Quarterly, 35 (1990): 61-103.

8. Benjamin, Robert, and Micahel Scott Morton (1992), "Reflections

of Effective Apllication of Information Technology.." in F.H. Vogt

(Ed.), Personal Computers nd Intelligent Systems, Information

Processing 92, Vol. III. North Holland: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

9. Burns, Tom, and G.M. Stalker (1961), The Management of

Innovation. London, UK: Tavistock Publications Limited.

10. Carter, Nancy M., (1984), "Computerization as a Predominate

Technology: Its Influence on the Structure of Newspaper Organizations",

Academy of Management Journal, vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 247-270.

11. Chandler, A.D. (1962), Strategy and Structure. Cambridge, MA:

The MIT Press.

12. Child, John (1987), Information Technology, Organization, and

the Response to Strategic Challenges", Californaia Management

Review, Fall, 33-50.

13. Davis, Fred D. (1989), Perceived Usefulness, "Perceived Ease

of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology," MIS Quarterly,

September(1989), 319-340.

14. Dawson, P., and I. McLaughlin (1986), "Computer Technology and

and the Redefinition of Supervision: A Study of the Effects of

Computerization on Railway Freight Supervisors,"

Journal of Management Studies, 23(1986), 116-132.

15. Dhar, Vasant, and Margrethe H. Olson (1989), "Assumptions

Underlying Systems That

Support Work Group Collaboration," in Margrethe H. olson, ed., Technological Support for

Work Group Collaboration. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1989, pp.

33-50.

16. Drucker, Peter F. (1988), "The Coming of the New Organization,"

in The New Realities In

Government and Politics, In Economics, In Society and World View New York: Harper &

Row. 2nd ed., 1990.

17. Foulger, Davis A. (1990), "Medium as Process: The Structure,

Use and Practice of

Computer Conferencing on IBM's IBMPC Computer Conferencing Facility", unpublished

doctoral dissertation defended at the Temple University, August 1990.

18. Guttiker, Urs E., and Barbara A. Gutek (1988), "Office

Technology and Employee

Attitides", Social Science Computer Review, 6(3), 327-340.

19. Handy, Charles (1989), The Age of Unreason. Boston, MA: Harvard

Business School Press.

20. Hiltz, Starr Roxanne (1984), Online Communities: A Case Study

of the Office of the Future. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Co.

21. Huber, George P. (1990), "A Theory of the Effects of Advanced

Information Technologies

on Organizational Design, Intelligence, and Decision Making", Academy of Management

Review, 15, 1, 47-71.

22. Kahn, Robert L., D.M. Wolfe, R.P. Quinn, J.D. Snoek, and R.A.

Rosenthal (1964), Organizational Stress. New York: Wiley.

23. Keon, Thomas L., Gary S. Vazzana, and Thomas E. Slocombe

(1992), "Sophisticated

Informatin Processing Technology: Its Relationship wirh an Organization's Environment,

Structure and Culture", Information Resources Management Journal, 5(4), 23-31.

24. Kerr, E.B., and S.R. Hiltz (1982), Computer-Mediated

Communication Systems: Status

and Evaluation. New York: Academic Press.

25. Kiesler, Sara, Jane Siegel, and Timothy W. McGuire (1984),

"Social Psychological

Aspects of Computer-Meditaed Communciation", American Psychologist, 39(10),

1123-1134.

26. Lawrence, Paul, and J.W. Lorsch (1967), Organization and

Environment: Managing

Differntiation and Integration. Boston: Harvard Business School.

27. MacDonald, A.P., Jr., Vicki S. Kessel, and James B. Fuller

(1972), "Self-Disclosure and

Two Kinds of Trust," Psychological Reports, 30, 143-148.

28. Markham, W.T., C.M. Bonjean, and J. Corder (1984), "Measuring

Organizational Control: The Reliability and Validity of the Control

Graph Approach," Human Relations, 37, 263-294.

29. Mills, D.Q. (1991), Rebirth of Corporation. New York: J. Wiley

h Sons.

30. Mintzberg, Henry (1979), The Structuring of Organizations: A

Synthesis of the Research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

31. Mintzberg Henry and Alexandra McHugh (1985), "Strategy

Formation in an Adhocracy," Adminstrative Science Quarterly, 30,

160-197.

32. Morgan, Gareth (1989), Creative Organization Theory: A

Resourcebook. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

33. Morgan, Gareth (1993), Imaginization: The Art of Creative

Management. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

34. Oldham, G.R., and J.R. Hackman (1981), "Relationships between

Organizational Structure

and Employee Reactions: Comparing Alternative Frameworks," Administrative Science

Quarterly, 26, 66-83.

35. Olson, Margrethe H., and Sara A. Bly (1991), "The Portland

Experience: A Report On a

Distributed Research Group", International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 34, 211-228.

36. Orlikowski, Wanda (1992), "The Duality of Technology:

Rethinking the Concepts of

Technology in Organizations," Organization Science, Vol. 3, No. 3, Augist 1992,

398-427.

37. Peters, Tom (1992), Liberation Management: Necessary

Disorganization for athe

Nanosecond Nineties. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

38. Pfeffer, Jeffrey and Huseyin Leblebicvi (1977), "Information

Technology and

Organizational Structure", Pacific Sociological review, 20(2), 241-260.

39. Pool, Ithiel de Sola (1983), Forectasting the Telephone: A

Retrospective Technology

Assessment. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

40. Powell, Walter W. (1990), "Neither Market Nor Hierarchy:

Network Forms of

Organization," in Barry M. Staw, and L.L. Cummings (eds.), Research in Organizational

Behavior, 12, 295-336.

41. Powell, Walter W., and Peter Brantley (1992), "Competitive

Cooperation in

Biotechnology: Learning Through Networks", in Nohria and Eccles (1992), 366-394.

42. Quinn, James Brian (1992), Intelligent Enterprise: A Knowledge

and Service Based

Paradigm for Industry. New York: The Free Press.

43. Rizzo, John R., Robert J. House, and Sidney I. Lirtzman (1970),

"Role Conflict and

Ambiguity in Complex Organizations," Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 15,

150-163.

44. Rockart, John F., and James E. Short (1991), "The Networked

Organization and the Management of Interdependence", in [46].

45. Rotter, Julian B. (1967), "A New Scale for the Measurement of

Interpersonal Trust," Journal of Personality, 35, 651-665.

46. S. Scott Morton, Ed., The Corporation of the 1990s: Information

Technology and

Organizational Transformation. Oxford: oxford University Press.

47. Schein, Edgar H., (1991), "What Is Culture," in Peter J. Frost,

Larry F. Moore, Meryl Reis

Louis, Craig C. Lundberg, and Joanne Martin (eds.), Reframing Networked Organization.

Cambridge, MA; The MIT Press.

48. Shapiro, Norman Z., and Robert H. Anderson (1985), "Toward an

Ethics and Etiquette for Electronic Mail", Rand Corporation.

49. Siegel, Jane, Vitaly Dubrovsky, Sara Kiesler, and Timothy W.

McGuire(1986), "Group

Processes in Computer-Mediated Communication," Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 37, 157-187.

50. Smilowitz, Michael, D. Chad Compton, and :yle Flint (1988),

"The Effects of Computer

Mediated Communication on an Individual's Judgement: A Study Based on the Methods of

Asch's Social Influence Experiment", Computers in Human Behavior, 4, 311-321.

51. Smolensky, Mark W., Meghan A. Carmody, and Charles G. Halcomb

(1990), "The

Influence of Task Type, Group Stucture and Extraversion on Unhibited Speech in

Computer-Mediated Communication," Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 261-272.

52. Sproul, Lee, and Sara Kiesler (1986), "Reducing Social Context

Cues: The Case of

Electronic Mail", Management Science, 32, 1492-1512.

53. Sproul, Lee, and Sara Kiesler (1991), Connections: New Ways of

Working in the

Networked Organization. Cambridge, MA; The MIT Press.

54. Stevens, Mark (1981), The Big Eight. New York: Macmilan

Publishing Co., Inc.

55. Stevens, Mark (1985), The Accounting Wars. New York: Macmilan

Publishing Co.

56. Tanenbaum, Arnold (1961), "Control and Effcetiveness in a

Voluntary Organization",

American Journal of Sociology, 67, 33-46.

57. Tetlock, Philip E. (1983) "Accpiuntability and Complexity of

Thought", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 74-83.

58. Watson, D.J.H. (1975), "The Structure of Project Teams Facing

Differentiated

Environments: An Exploratory Study in Public Accounting Firms", The Accounting Review,

April, 259-273.

59. Weber, Max (1946), Essays in Sociology. Oxford University

Press.

60. Whisler, Thomas L. (1970), The Impact of Computers on

Organizatins. New York: Praeger.

61. Wigan, M. (1991), "Computer-Cooperative Work: Communications,

Computers and Their

Contribution to Working in Groups". In Roger Clarke and Julie Cameron (eds.), Managing

Information Technology's Organisational Impact. Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 15-24.

62. Wigand, Rolf T. (1985), Integrated Communications and Work

Efficiency: Impacts on

Organizational Structure and Power. Paper presented at: Beyond Polemics:

Paradigm Dialogues:

International Communication Association 35th Annual Conference. May 23-27, 1985,

Honolulu, HI.

63. Wijnhoven, A.B.J.M. and D.A. Wassenaar (1990), "Impact of

Information Technology on

Organizations: The State of the Art", International Journal of Information Management, 10,

35-53.

1. Adams, Dennis A., R. Ryan Nelson, and Peter A. Todd (1992), "Perceived Usefulness, Ease of

Use, and Usage of Information Technology," MIS Quarterly, June(1992), 227-247.