|

PAPERS

An

Evolutionary Theory of Education

Joseph J. Pear

Department

of Psychology, University of Manitoba,

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2

Abstract

The capacity to learn

is a product of evolution, in that it promotes survival

and the perpetuation of an individual's genetic material.

An individual that can learn can be taught. Hence, a next

step in evolution was teaching of the young by caretakers

(usually the parents). Training of the young is carried

out in many species but has evolved to its highest degree

in humans. Humans also possess language, which has enabled

them to develop complex cultures. These cultures perpetuate

themselves and compete for resources and for members. This

competition leads to the evolution of cultures similar to

the manner in which species evolve. Education is analogous

to the reproductive system; it is the mechanism by which

cultures perpetuate themselves. Eventually in cultural evolution,

education became institutionalized in some human cultures

because of the evolutionary advantages it provided to those

cultures. Educational techniques, however, have changed

very little since ancient times despite research showing

that some educational techniques are superior to others.

Despite this resistance to change, certain applications

of computer-based technology may provide the next step in

the cultural evolutionary process.

An

Evolutionary Theory of Education

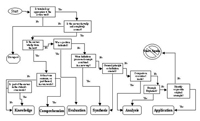

The theory of education

with which this paper deals considers evolution of education

and culture as a natural process. Being based on learning,

the evolution of education is based in the evolution of

species. We therefore first consider the evolution of learning.

We then consider the evolution of training, which is carried

out by many species in which parental and other care of

the young is provided. We next discuss how this training

is most advanced in humans, largely because of they have

evolved a facility for complex language. It is this ability

that makes human cultures and institutionalized education

possible. The paper concludes by considering what the next

step in educational and cultural evolution might be.

The

evolution of learning

Along with other

properties of organism, the capacity to learn is a product

of evolution. Learning occurs because it promotes the propagation

of the genetic code of the organism that possesses the capacity

to learn (see Pear, 2001). There are several types of learning,

including sensitization, habituation, imprinting, classical

or respondent conditioning, and instrumental or operant

conditioning. Of these, it is the last with which we are

concerned here; roughly speaking, operant conditioning is

the modification of behavior by its consequences. Education

is mostly concerned with changing behavior by arranging

for favorable consequences to follow desirable behavior.

For example, when a student's excellent essay receives praise

from the teacher, we expect that the student will write

praiseworthy essays in the future.

Operant conditioning

evidently appeared quite early in evolutionary history.

It exists in the earliest vertebrates. Any one who has kept

fish knows that they swim expectantly to the sight or sound

of someone getting ready to feed them. This is operant conditioning,

because the fish receives the food faster if it is nearer

the location in which the food enters the water. Fish will

also learn to push a response key if this results in food

dropping into the fish tank (Talton, Higa & Staddon,

1999). The operant conditioning of similar responses in

rats, pigeons, and monkeys is well known to every student

in an introductory psychology course. What is perhaps not

so well know is the pervasiveness of operant conditioning;

it occurs in organisms whose evolutionary paths diverge

considerably from that of the vertebrates. For example,

it occurs in insects, such as ants (Schneirla, 1943) and

honey bees (Grossman, 1973). Since these invertebrates have

nervous systems that are quite different from those of vertebrates,

there is a suggestion that the ability to learn through

operant conditioning may have evolved independently in different

genetic lines.

The evolutionary

advantage of operant conditioning is fairly obvious in a

changing environment. A location that once provided food

may no longer do so; an unfamiliar potential prey item may

turn out to provide a nutritious meal or an illness-producing

toxin. Another unfamiliar animal may turn out to be relatively

harmless or a dangerous predator. An animal that is to survive

and pass on its genetic material must adjust to these diverse

circumstances, and learning obviously permits it to do so.

What may not be so obvious, however, is the connection this

all has to education. Physical survival does not usually

depend on being able, for example, to write a commendable

essay. However, the same process that enabled our ancestors

learn to how to hunt efficiently can be enlisted to enable

us to learn to write effectively. Both involve small shaping

steps punctuated by positive feedback. In the case of hunting,

the feedback was from the physical environment (a successful

kill) and from other humans (praise for performing actions

that led to a successful kill). In the case of essay writing,

the shaping steps and feedback is from the teacher, who

incidentally has been operantly conditioned to provide this

feedback.

Training of the

young

For many species,

the parental function consists simply in reproduction. For

certain others (i.e., those unable to fend for themselves

at birth), however, there is care-giving from one or both

parents and perhaps other members of the social group, until

the young are able to make it on their own. Inevitably,

animals learn from their caretakers and other members of

their social group, but most of this learning occurs incidental

to other activities. There is no deliberate attempt to teach.

In some cases, deliberate teaching appears to occur but

can be explained as phylogenetic; e.g., a mother lion teaching

her young to hunt or a bird teaching its young to fly. Although

the teacher may employ sound pedagogical principles (e.g.,

shaping, fading, scaffolding), their utilization has been

developed by evolution rather than by learning.

Moving up the phylogenetic

scale we do not find any evidence for deliberate teaching

until we come to the apes, most notably our closest relatives,

chimpanzees. These animals engage in certain complex tool-use

behaviors, such as termite fishing (with a long stem inserted

into a termite hole) and nut cracking using a hammer-and-anvil

technique (using two stones). These are complex skills that

take many years to perfect. There is some evidence of mothers

actively teaching their young (thought physical guidance)

proper techniques in performing these skills ( ). ).

Only humans show

clear evidence of deliberate systematic teaching. The earliest

evidence of this is from between 11,000 and 15,000 years

ago. The stone chips found around certain stone-age hearths

shows that evidence a master stone chipper encircled by

learners who practiced the master's demonstration of the

proper way to chip out stone tools, such as axes and knives

(Fisher, 1990; Pigeot, 1990). Hence, humans carried out

classroom-style teaching as early as 11,000 years ago.

Although there was

no permanent record of it, these early teachers were undoubtedly

doing more than merely demonstrating and the students were

not merely imitating. The teacher undoubtedly was providing

verbal instruction and reinforcement, and the students were

responding to that instruction and reinforcement. The human

propensity for speaking and listening – for language

– probably evolved from early social bonding (Dunbar,

1991, 1993). In primates social bonding occurs though physical

contact (e.g., grooming) and vocalizations. Language developed

when humans evolved the capacity to imbed information more

complex than simple "stroking" (e.g., the equivalents of

"how are you?" and "fine, thank you") in their physical

gestures and vocalizations. Language enabled the development

of human cultures.

Cultures

We may define a culture

as a set of learned practices (including laws, values, ways

of doing things) passed on from one generation to the next.

Cultures evolve in a manner similar to the way in which

species evolve (for discussions of cultural evolution and

values, see Handy, 1960; Pepper, 1958, 1960; Skinner, 1953,

1971). Some cultures are well adapted to their environments

and survive. Others are not well adapted and perish. Part

of a culture’s environment includes other cultures.

Hence cultures compete in a manner similar to that in which

species compete. A culture survives only if it has members

that survive and perpetuate it. Hence, cultures compete

for resources and for members.

The practices of

a culture may promote or hinder its survival. Some practices

are more successful in promoting a culture's survival than

others are. Some practices are harmful, and may lead to

the demise of a culture. Some practices are not beneficial,

or may even be harmful, but the culture may nevertheless

survive for a long time because other practices counteract

them or because no competing culture is present to exploit

those weaknesses.

Education

If a culture is analogous

to a species, then education is the reproductive system

of a culture. Just as the reproductive system is responsible

for transmitting traits from one generation to the next,

education replicates or transmits cultural practices, including

values, rules, laws, customs, and skills. Also included

in the practices of a culture is its social structure.

Education mirrors

the culture in which it occurs. If the technology and social

structure of a culture is relatively simple, education is

simple. In a "simple" culture, education consists of the

young learning from other members simply by participating

in the activities of the culture. As the technology and

social structure become more complex, special instruction

becomes necessary. Chipping stone tools is a difficult skill

but vital to a stone-age culture, hence classes apparently

were required to facilitate members learning it.

A number of cultures

developed a degree of complexity in which members are stratified

into several strata or classes. These might include slaves

(e.g., ancient Greece, ancient Rome, the United States before

the Civil War), and lower, middle, and upper classes. Slaves

received virtually no education, the lower classes might

receive some sort of vocational training (often in the form

of apprenticeships), the middle classes received training

needed to be merchants, government administrators, and teachers,

while the upper classes received training that enabled them

to rule more effectively. Simplifying somewhat, universities

developed to fulfill these last-two mentioned functions

(Barzunm 2000, pp. 228-229). Complex verbal behavior, including

the ability to discuss, reason, and argue are always useful

to the governing and ruling classes. Even in the upper classes,

women throughout all complex (stratified) societies, up

until recent times, received only enough education to enable

them fulfill the roles of mothers and homemakers. It is

clear that education served to maintain the social structure

of these cultures.

As described above,

a culture may perpetuate itself by spreading its practices

to succeeding generations. Another way it may perpetuate

itself is by invading other cultures and attempting to transform

them into replicas of itself (the analogy of a virus invading

a cell comes to mind here). This is imperialism, which has

been practiced so successfully by Western countries. True

to its function as a replicator, education has been critical

in the success of imperialism. The transplanting of the

invaders’ educational systems into other countries

(or, alternatively, sending members of the "host" country

to be educated in the invading country) is analogous to

the transplanting of viral DNA into host cells. That is,

largely as a result of the transplantation of the invader's

educational system into the host, the host country becomes

more like the invader. It is interesting to note that this

ultimately works to the disadvantage of the invader, because

once the ruling members of the host are sufficiently educated

in the practices of the invader, the host country tends

to declare its independence. Similarly, the transfer of

genetic material through sexual reproduction does not necessarily

work to the advantage of the individual making the transfer.

In some cases the

educational system of an invading country has been used

to obliterate (or come close to obliterating) an indigenous

culture. A prime example is the forcible removal of Native

children from their parents and the placement of these children

in residential schools, which occurred in Canada. Forced

to learn the language and practices of the dominant culture,

the children in these schools were severely punished for

speaking their own language and were kept from learning

anything about their own culture.

Conflict between

dominant and subordinate groups over education

Since education tend

to preserve the social order, members below the ruling class

strive to obtain educational opportunities that would allow

them to move into a higher class. The middle class presses

for access to universities. The lower class presses to obtain

basic education such as instruction in reading. And women

press to obtain the same educational privileges men enjoy.

Cultural changes

also help to bring about changes in the availability of

education. By promoting the idea that each individual should

be able to interpret the Bible for him or herself, leaders

of the reformation successfully diminished the power of

the Catholic Church. However, this idea makes sense only

if everyone can read the Bible. The logical consequence

of the change in the culture brought about through the reformation

was that education in reading should be available to all.

For the first time, therefore, government was in the position

of having to provide universal education.

With the industrial

revolution, a skilled labor force was needed. In addition,

to protect the upper classes from social disruption and

mayhem, youthful industrial workers needed to be occupied

during the times that they were not at work. Hence, universal

education was implemented on Sundays, and gradually extended

to other days of week.

In more recent times,

members of minority cultures have successfully petitioned

to right to educate their members in their own culture.

Politicians have responded favorably to this as means of

winning votes and diffusing tensions.

Conflict between

educators and the state

The state –

i.e., the governing or ruling body of a culture –

attempts to use the educational system to preserve itself.

Dissidence is not to be tolerated if the ruling body has

any say in the matter. This can bring the educational system

into conflict with the state, and with the education administration

– the representatives of the state within the educational

system. One way in which this conflict appears is in the

struggle within the educational system between those who

favor restrictions on what can be taught and those who advocate

academic freedom. Two important activities of education,

at least as it exists today, are examining new ideas and

questioning the status quo. These activities, however, can

threaten the stability of the culture, and therefore tend

to be resisted by those outside the educational institution

(and often by some within). In the long run, similar to

favorable mutations, the new ideas that are developed and

promulgated in the educational institutions may lead to

changes in cultural practices that strengthen the culture.

This is why academic freedom has become a firmly entrenched

value in some cultures, although it is still suspect in

others.

The Shifting

Role of Educators

Ever since the printing

press was invented and books became widely available, lectures

have been largely redundant. This is not to say that lectures

have no value. In many cases they can be very beneficial.

But they are not of equal value for everyone; and there

are some who are able to learn quite well just by reading.

Suppose, however, that a student went to the president of

a university and said, "I have read every book in your library;

please have your faculty test me and if I pass give me a

degree." It is highly unlikely that such a student would

have his or her request granted. At best the student might

be granted an exemption from a few classes, but would have

to sit through many more. Educators can rationalize this

requirement in a number of ways; however, a case can be

made that the underlying reason for it is that such a student

is seen as a threat. It represents a loss of power. If you

can learn without having to sit in our classrooms and listen

to our lectures, then we have no power over you.

Some educators may

also see the new technology of web-based instruction as

a threat. Students on line do not have to be in the classroom.

Some educators have attempted to adapt the lecture method

to the new technology. In this format, students "meet" at

a specified time, read a text-based "lecture" prepared by

the instructor, and engage in online discussion by typing

in comments on the lecture and comments on other students

comments. This approach has the advantage that students

do not have to be physically present on campus in order

to take a course. This results in an increase in the number

of people who can take courses and receive the benefits

of education.

More could be done

for students by taking advantage of research findings on

different educational techniques. The data are quite consistent

in indicating that mastery learning methods and cooperative

learning work far better than lectures (Kulik, Kulik, &

Bangert-Drowns, 1990). Real advances in education may occur

when these methods are combined with web-based technology

(for perhaps a start in this direction, see (Crone-Todd,

Pear & Read, 2000; Pear & Crone-Todd, 1999; Pear

& Novak, 1996). Given that educational practices have

changed very little since the days of Socrates, despite

many attempts to improve them over the centuries, it is

probably unwise to predict that fundamental change will

occur anytime soon. However, although educators have been

strongly conditioned to preserve their traditional practices,

they have also been conditioned to work for the betterment

of their culture. The advances in technology that rapidly

are making all forms of information widely available to

everyone may demand new approaches to education. The next

large evolutionary jump in education may be at hand.

References

Barzun, J. (2000).

From dawn to decadence: 1500 to the present. New York:

HarperCollins.

Boesch, C. Teaching

among chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour, 41, 530-532.

Crone-Todd, D.E.,

Pear, J.J., & Read, C.N. (2000). Operational definitions

for higher-order thinking objectives at the post-secondary

level. Academic Exchange Quartlery, 4, 99 -106.

Dunbar, R. I. M.

(1991). Functional significance of social grooming in primates.

Folia Primatologica, 57, 121-131.

Dunbar, R. I. M.

(1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and

language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16,

681-735.

Fisher, A. (1990).

On being a pupil of a flint knapper 11,000 years ago. A

preliminary study of settlement organization and flint technology

based on conjoined flint artifacts from the Trollesgave

site. In E. Cziesala, S. Eickhoff, N. Arts, & D. Wiunter

(Eds.), The big puzzle: International symposium on refitting

stone artefacts (pp. 447-464). Bonn: Holos.

Grossman, K. E. (1973).

Continuous, fixed-ratio, and fixed-interval reinforcement

in honey bees. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of

Behavior, 20, 105-109.

Handy, R. (1969).

Value theory and the behavioral sciences. Springfield,

IL: Thomas.

Kulik, C.-L. C.,

Kulik, J. A., & Bangert-Drowns, R. L. (1990). Effectiveness

of mastery learning programs: A meta-analysis. Review

of Educational Research, 60, 265-299.

Pear, J. J. (2001).

The science of learning. Philadelphia: Psychology

Press.

Pear, J. J., &

Crone-Todd, D. E. (1999). Personalized system of instruction

is cyberspace. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32,

205-209.

Pear, J. J., &

Novak, M. (1996). Computer-aided personalized system of

instruction: A program evaluation. Teaching of Psychology,

23, 119-123.

Pepper, S. C. (1958).

The sources of value. Berkeley: University of Calgary

Press.

Pigeot, N. (1990).

Technical and social actors: Flint knapping specialists

and apprentices at Magdalenian Etiolles. Archaeological

Review Cambridge, 9, 126-141.

Schneirla, T. C.

(1943). The nature of ant learning: II. The intermediate

stage of segmental maze adjustment. Journal of Comparative

Psychology, 34, 149-176.

Skinner, B. F. (1953).

Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1971).

Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf.

Talton, L. E., Higa,

J. J., & Staddon, J. E. R. (1999). Interval schedule

performance in the goldfish Carassius auratus. Behavioural

Processes, 45, 193-206.

|

|

|