The IPA |

The IPA |  Writing things the way they sound |

Writing things the way they sound |  Transcription |

Transcription |  Home

HomeSeveral writing systems have been developed which are more concerned with how a word sounds than with how it has traditionally been spelled.

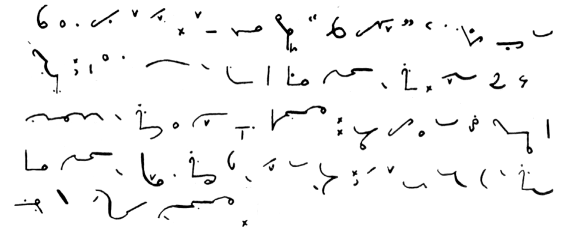

Many of the shorthand systems developed for English in the last couple of centuries (such as Pitman shorthand, pictured here) use the idea of writing down words the way they sound, rather than the way they are spelt -- a large motivation being the time saved in not writing silent letters. Early shorthand systems were one inspiration for 19th-century phoneticians.

English dictionaries usually give the pronunciation of a word as part of its entry. In most Webster's dictionaries, for example, you will find the pronunciation of knight given as "nīt" and cat as "kăt". In order to understand these pronunciation entries, you have to learn what sounds are meant by symbols like "ī" and "ă".

As consistent as these can be made for a single dialect of English, both shorthand systems and the traditional dictionary pronunciation keys will suffer from the same problems as ordinary spelling conventions when it comes to representing the differences between dialects or non-English sounds.

A more radical solution is to create an entirely new alphabet. Several proposals for new phonetic alphabets have been made over the centuries, for example:

Most of these alphabets consisted of entirely new characters, making them fairly hard to learn. The only alphabet systems that ever caught on were the ones that kept as many symbols from the familiar Roman alphabet as possible, such as the informal transcription system developed by North American linguists and the formal, standardized International Phonetic Alphabet.

Professional linguists, particularly those in the North American tradition, haphazardly developed over the last century a collection of symbols for use in phonetic transcriptions. Many of these are identical to the symbols used in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), but there are also several differences. For example, the "sh" sound of English is written [ʃ] in the International Phonetic Alphabet, but was usually written [š] by North American linguists. Many of these differences made it easier to type the symbol on a typewriter -- instead of leaving a space where an [ʃ] should have been and writing in in by hand later, you could type an ordinary [s] and only have to put in the check mark by hand later.

Unfortunately, this set of transcription conventions was never standardized. While some of the symbols (like [š]) were used the same way by almost everybody, most were not. If you read a symbol in a linguistics article or book, you could never be certain what sound it was supposed to represent.

Now that typewriters have gone the way of vinyl records and computers make it just as easy (or just as hard) to type a standard IPA [ʃ] as a non-standard [š], even grouchy North Americans have been abandoning the informal system for the IPA. (There are still hold-outs, of course, just like there are still people who will never till their dying breath use the metric system. C'est la vie.)