PSYC 1200 Academic Achievement Assignment Summary

Dear Student,

Now that you've finished the academic achievement assignment for your introductory psychology course,

we would like to take a little time to introduce some of the research surrounding the assignment you completed.

This assignment has been developed from concepts grounded in over two decades of research conducted by the

Motivation and Academic Achievement (MAACH) lab. One of the core ideas that has guided this research can

be expressed by the notion that you do not need to be an "Einstein" or intellectual genius to do well in university.

For example, using high school grades as an indicator of aptitude, our past studies suggest that ability

only accounts for about 25% of the variability in university grades. Therefore, 75% of the variability

in grades is due to other things besides natural aptitude!

One of the other things that we have repeatedly found to be important is perceived control,

which refers to the perception people have of being able to influence important outcomes in their lives,

such as exam performance (i.e., feeling "in" or "out" of control). Our continuing research within the

university setting has shown that the perception of control accounts for about 10% of variability in student

grades. Although 10% doesn't sound like much, it can actually make the difference between a "C" and a "B," or even a "B" and an "A"!

Thus, within the MAACH lab we ask the question: If the perception of control is so important, how can

we minimize feeling "out of control" and maximize feeling "in control"? Well, to begin with, whenever

something negative happens to us, we engage in a mode of thinking that psychologists call causal

search. In other words, we want to know why the event took place, so we search for

causes or reasons for the event, hopefully so we can prevent it from happening again.

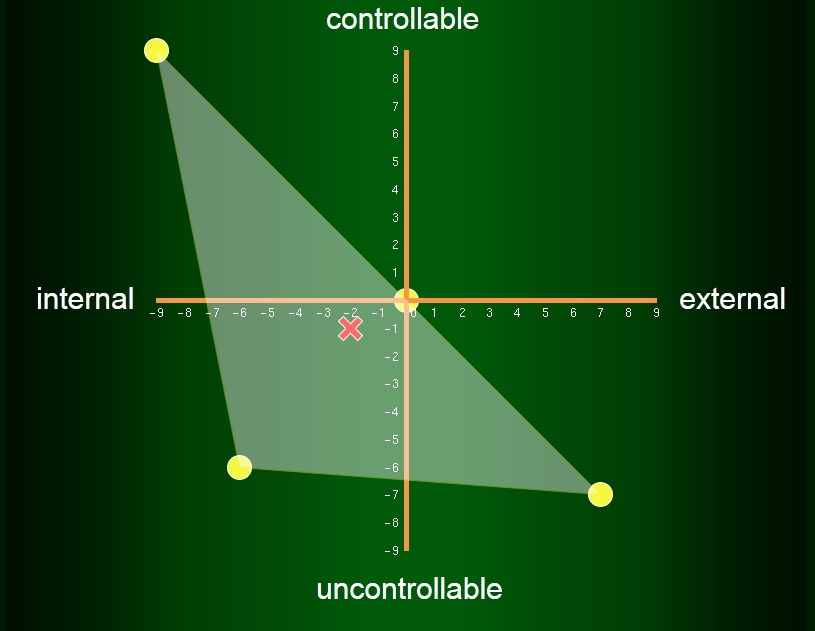

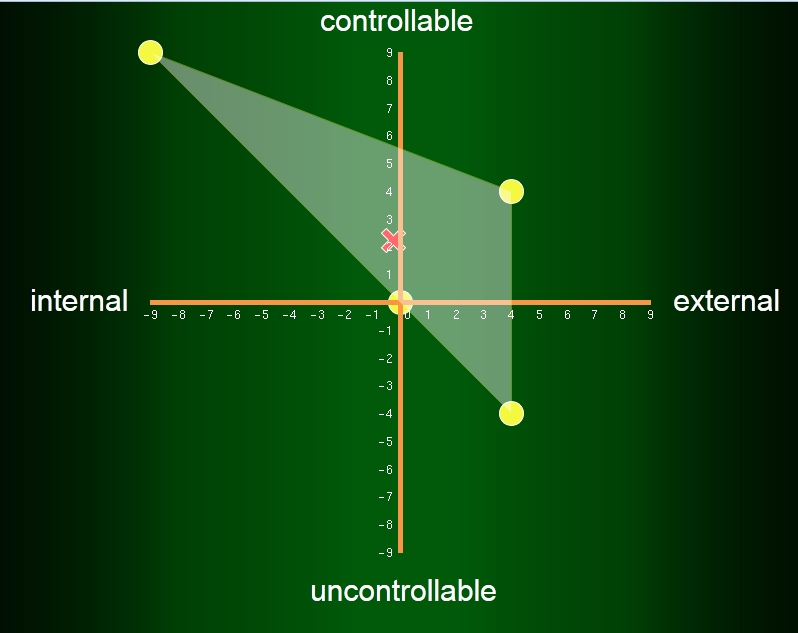

Once a cause has been determined, there are two main dimensions that we use to "classify" the

causes we find. The first dimension is called the locus (location) of the cause ("internal" -

that is - "inside" of ourselves vs. "external" or "outside" of ourselves). The second dimension is called

controllability, which refers to whether or not a cause is under our control.

Let's take a look at how your attributions can be represented in a simple schematic with four basic

quadrants, as the graphs below demonstrate. Now as an example, consider the kinds of attributions that could

be made for getting a bad mark on a test: We could believe the cause to be a lack of natural ability,

which would be internal-uncontrollable because it's something inside ourselves that we're born with

(bottom, left quadrant). However, we could just as easily attribute our failure to lack of effort put into

studying, which would may be considered internal-controllable because effort comes from "inside

ourselves" and we can control the amount of effort we put toward studying (top, left quadrant). It is also

possible to say that we had too many other commitments, which could be classified as external-controllable

because it is outside ourselves but we have choices when it comes to how we prioritize our time (top, right quadrant).

Finally, we might also say that it was due to course requirements that were too difficult, which could be

thought of as external-uncontrollable because it is outside of ourselves and uncontrollable (bottom, right quadrant).

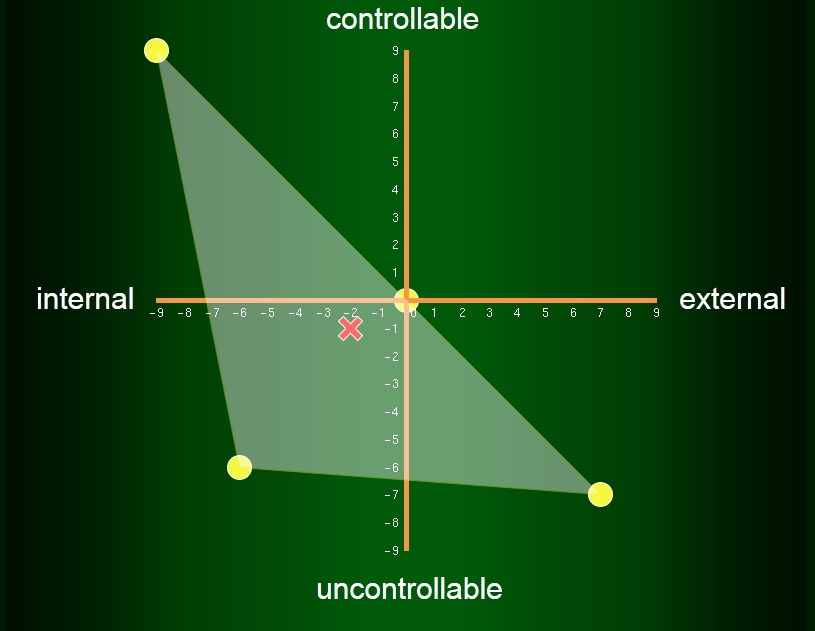

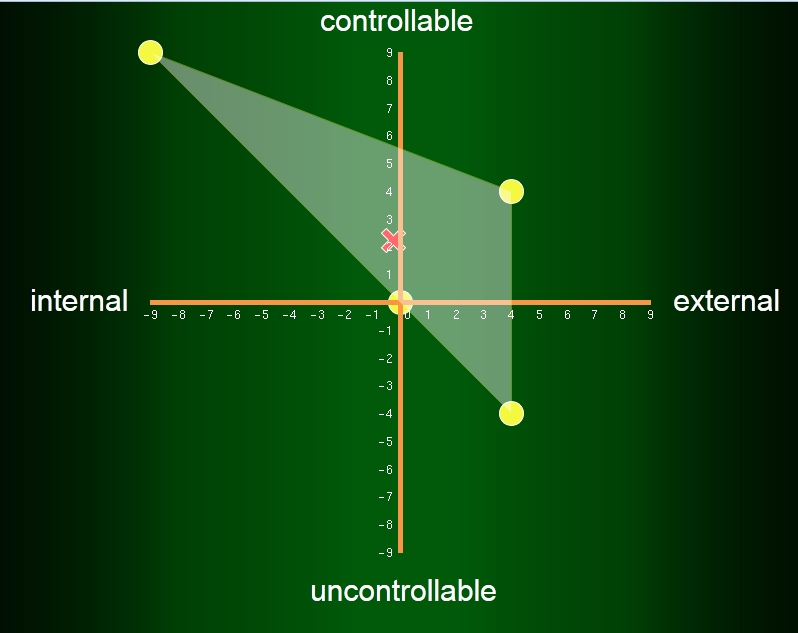

Part 1 (1st Term)

Part 2 (2nd Term)

As you can see from the graphic on the right, our previous research shows that students who completed the academic achievement

assignment made many fewer internal-uncontrollable attributions (such as lack of ability) during Part 2 of the assignment

(second term) than they did during Part 1 of the assignment (first term).

This shift in the way students classify their causes for failure is an important point because as we mentioned

before, the types of attributions we make affect our perceptions of control, motivation, and academic achievement.

For example, if we attribute failure to reasons that we believe are uncontrollable, like not having enough natural ability

for university, we can demoralize ourselves to the point of simply "giving up"; we stop trying because we feel there's

nothing we can do. Therefore, it is more productive to attribute failure to controllable causes, especially

internal-controllable causes such as lack of effort or a poor study strategy. Thus, the assignment seems

to be one way of positively altering students' attributions which not only affects motivation, but also

future academic success!

In summary, the long-term goal of this assignment was to help you adjust to university life and to achieve better

grades in your courses. However, psychological science rarely, if ever, comes up with "sure fire" 100% guaranteed techniques that

apply to everyone or work all the time because individuals vary so widely. That being said, students who persist

in trying to gain control over their own learning processes, on average, are more likely to be successful in the long run

than students who rely only on their natural ability alone. So, it is important to choose controllable attributions

(such as not putting enough effort into studying) in order to maintain perceived control and stay motivated!

Finally, on behalf of your PSYC 1200 instructors, we would like to thank you for completing the assignment. If you have

any further questions about the research surrounding this assignment, please feel free to contact Jeremy Hamm

(Jeremy.Hamm@umanitoba.ca) in the Department of Psychology.

The MAACH Team

|