All-Time List of Canadian Transit Systems

by David A. Wyatt

5.0 Index of Communities By Transit Modes

Sometime called “Regional Rail”. Commuter trains are passenger trains operating on the

general railway network, within an urban area or between an urban centre and it's outlying

suburban communities. Principal passenger community is persons making same-day return trips within an

urban metropolitan area.

Sometime called “Regional Rail”. Commuter trains are passenger trains operating on the

general railway network, within an urban area or between an urban centre and it's outlying

suburban communities. Principal passenger community is persons making same-day return trips within an

urban metropolitan area.

- Montréal, Québec

- Toronto, Ontario

- Vancouver, British Columbia

The RegioSprinter-operated service in Calgary, Alberta during

the summer of 1996 could be considered “commuter rail” or “diesel light rail”. A technologically

similar diesel light rail service began operating in Ottawa, Ontario in October 2001.

The railbus operated at Lillooet might also be considered commuter rail.

The above list does not include commuter rail services operated directly by

railways prior to the period of Transit Agency involvement, which remains to be fully documented. Notes may

be found under

1. Elmira, Ontario,

2. Fort Erie, Ontario,

3. Halifax, Nova Scotia,

4. Kings County - Hants County,

5. Miramichi, New Brunswick,

6. Moncton, New Brunswick,

7. Montréal, Québec,

8. Pictou, Nova Scotia,

9. Portneuf - Québec, Québec,

10. Regina, Saskatchewan,

11. Renfrew, Ontario,

12. Saint John's, Newfoundland & Labrador,

13. Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Québec

14. Shawinigan, Québec,

15. Sydney, Nova Scotia,

16. Toronto, Ontario,

17. Transcona, Manitoba,

18. Victoria, British Columbia,

and

19. West Vancouver, British Columbia.

See also Storage battery cars.

Via Rail Canada, Inc., Canada's national passenger railway, offers commuter fares (monthly

and ten-round-trip passes) for many station pairs.

Via's list is available here (2015).

Notes on Via's service can be found under Montréal, Ottawa, and Toronto.

5.2 Interurban Electric Railways

1. Brantford,

2. Chatham,

3-4. Galt [Cambridge] – Kitchener,

5. Temiskaming Shores,

6-9. Hamilton,

10. Hull [Gatineau],

11-12. London,

13. Montréal,

14. New Glasgow,

15. Niagara Falls,

16. Québec,

17. St. Catharines – Niagara Falls,

18. Sydney,

19. Thunder Bay‡,

20-21. Toronto,

22. Vancouver,

23. Victoria,

24-25. Windsor,

26. Winnipeg, and

26. Woodstock.

1. Brantford,

2. Chatham,

3-4. Galt [Cambridge] – Kitchener,

5. Temiskaming Shores,

6-9. Hamilton,

10. Hull [Gatineau],

11-12. London,

13. Montréal,

14. New Glasgow,

15. Niagara Falls,

16. Québec,

17. St. Catharines – Niagara Falls,

18. Sydney,

19. Thunder Bay‡,

20-21. Toronto,

22. Vancouver,

23. Victoria,

24-25. Windsor,

26. Winnipeg, and

26. Woodstock.

For a more detailed tabulation, see separate list.

This is based on the canonical list of Canadian interurban electric railways, as determined by John F. Due (see

References). Other authors (notably William D. Middleton) writing from a less

rigorous definition include a variety of suburban streetcar lines with interurban characteristics. Among these

are: Calgary [Ogden and Bowness Park lines], Winnipeg [St. Norbert and SRT lines],

Sudbury [Copper Cliff line],

Ottawa [Britannia line], Montréal [MP&I and MT lines],

and Québec [QC and Kent House lines].

‡ The Mount Mckay & Kakabeka Falls Railway was leased, electrified and operated by the Fort William city system 1923-1947 which it appears neither Due nor Middleton knew.

Also known as “subway”, “metro”, or “rapid transit”.

Also known as “subway”, “metro”, or “rapid transit”.

- Montréal, Québec (1966 - present)

- Toronto, Ontario (1954 - present) *

- Vancouver, British Columbia (1986 - present) *

* Vancouver's SkyTrain rapid transit system and the former Scarborough RT in Toronto are implementations of

a technology marketed initially as “ICTS” (Intermediate Capacity Transit System) and then later as

“ALRT” (Advanced Light Rapid Transit). The systems more closely resemble “small metros” than other

implementations of what has come to be called “light rail transit”.

During Expo '67 (the 1967 World's Fair) in Montréal,

a separate heavy rail rapid transit system,

the Expo Express,

was operated to transport visitors to the fair site.

Technological modern descendant of the electric street railway,

often featuring very little mixed-traffic street running.

Technological modern descendant of the electric street railway,

often featuring very little mixed-traffic street running.

- Calgary, Alberta (1981 - present)

- Edmonton, Alberta (1978 - present)

- Kitchener, Ontario (2019 - present)

- Ottawa, Ontario (2001 - present) [diesel], (2019 - present) [electric]

The surviving street railway (tramway) in Toronto, Ontario also qualifies as

“light rail transit” by most definitions. The railbus service between Lillooet and Seton Lake might also

be consider [internal combustion] light rail.

Some observers also classify the Vancouver SkyTrain and Toronto

Scarborough RT as light rail.

A light rail transit project is in an advanced construction phase in Mississauga . Design work is also underway for light rail in Hamilton, Ontario.

5.5 Electric Street Railways

1. Belleville,

2. Brandon,

3. Brantford,

4. Calgary,

5. Cornwall,

6. Edmonton,

7. Fort William,

8. Glace Bay,

9. Guelph,

10. Halifax,

11. Hamilton,

12. Hull [Gatineau],

13. Kingston,

14. Kitchener – Waterloo,

15. Lethbridge,

16. Lévis,

17. London,

18. Moncton,

19. Montréal,

20. Moose Jaw,

21. Nelson,

22. New Westminster,

23. Niagara Falls,

24. North Sydney – Sydney Mines,

25. North Vancouver,

26. Oshawa,

27. Ottawa,

28. Peterborough,

29. Port Arthur,

30. Québec,

31. Regina,

32. St. Catharines,

33. Saint John,

34. St. John's,

35. St. Stephen,

36. St. Thomas,

37. Sarnia,

38. Saskatoon,

39. Sault Ste. Marie,

40. Sherbrooke,

41. Sudbury,

42. Sydney,

43. Toronto,

44. Trois-Rivières,

45. Vancouver,

46. Victoria,

47. Welland,

48. Windsor,

49. Winnipeg, and

50. Yarmouth.

1. Belleville,

2. Brandon,

3. Brantford,

4. Calgary,

5. Cornwall,

6. Edmonton,

7. Fort William,

8. Glace Bay,

9. Guelph,

10. Halifax,

11. Hamilton,

12. Hull [Gatineau],

13. Kingston,

14. Kitchener – Waterloo,

15. Lethbridge,

16. Lévis,

17. London,

18. Moncton,

19. Montréal,

20. Moose Jaw,

21. Nelson,

22. New Westminster,

23. Niagara Falls,

24. North Sydney – Sydney Mines,

25. North Vancouver,

26. Oshawa,

27. Ottawa,

28. Peterborough,

29. Port Arthur,

30. Québec,

31. Regina,

32. St. Catharines,

33. Saint John,

34. St. John's,

35. St. Stephen,

36. St. Thomas,

37. Sarnia,

38. Saskatoon,

39. Sault Ste. Marie,

40. Sherbrooke,

41. Sudbury,

42. Sydney,

43. Toronto,

44. Trois-Rivières,

45. Vancouver,

46. Victoria,

47. Welland,

48. Windsor,

49. Winnipeg, and

50. Yarmouth.

For a more detailed tabulation, see separate list.

5.6 Animal Street Railways

In most

cases the use of animal power on street railways in Canada included the use

of sleighs in winter. In some cities omnibuses were routinely used to

provide service during the Spring thaw.

In most

cases the use of animal power on street railways in Canada included the use

of sleighs in winter. In some cities omnibuses were routinely used to

provide service during the Spring thaw.

1. Belleville,

2. Brantford,

3. Chatham,

4. Halifax,

5. Hamilton,

6. Kingston,

7. Kitchener – Waterloo,

8. London,

9. Montréal,

10. Niagara Falls,

11. Ottawa,

12. Québec,

13. St. Catharines,

14. Saint John,

15. St. Thomas,

16. Sarnia,

17. Toronto,

18. Windsor, and

19. Winnipeg.

For a more detailed tabulation, see separate list.

Common carrier public passenger transport in an urban area using replica or restored antique

street railway cars.

Common carrier public passenger transport in an urban area using replica or restored antique

street railway cars.

- Calgary, Alberta (summers 1975 - present)

- Edmonton, Alberta (summers 1997 - present)

- Nelson, British Columbia (summers 1992 - present)

- Vancouver, British Columbia (summers 1998 - October 2008, summer 2011)

- Whitehorse, Yukon Territory (summers 15 July 2000 - 2019?)

See also Street Railway Operating Museums.

Electric buses powered from overhead wires.

Electric buses powered from overhead wires.

- Calgary, Alberta (1947 - 1975)

- Cornwall, Ontario (1949 - 1970)

- Edmonton, Alberta (1939 - 2009)

- Halifax, Nova Scotia (1949 - 1969)

- Hamilton, Ontario (1950 - 1992)

- Kitchener – Waterloo, Ontario (1947 - 1973)

- Montréal, Québec (1937 - 1966)

- Ottawa, Ontario (1951 - 1959)

- Regina, Saskatchewan (1947 - 1966)

- Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (1948 - 1974)

- Thunder Bay [Port Arthur – Fort William], Ontario (1947 - 1972)

- Toronto, Ontario (1922 - 1925 and 1947 - 1993)

- Vancouver, British Columbia (1948 - present)

- Windsor, Ontario (1922 - 1926)

- Winnipeg, Manitoba (1938 - 1970)

Trolley bus demonstration lines ran briefly in

Vancouver, British Columbia and

Victoria, British Columbia late in 1945.

For a listing of electric trolleybus systems in Canada, the United States of America, and

Mexico, see All-Time List of North American Trolleybus Systems.

The universal technology of urban public transit in Canada in the 20th century. Every

community in the All-Time List of Canadian Transit Systems with local transit

service has been served by buses, except perhaps St. Stephen, New

Brunswick, and sufficient research will probably uncover local bus service there too.

Early known examples of motor bus transit include

Montréal – Saint-Lambert in 1904,

Calgary in 1907, and

Leamington in 1910.

The earliest existing transit [streetcar] company to implement a bus service was

Brantford in 1916.

The first appearance of motorized road transit in many Canadian cities was jitneys. Beginning on the west coast

in late 1914, private automobile owners began using their cars to pick up fare-paying passengers. In some cities

hundreds of cars were engaged in the trade, jitney associations were formed, routes established, and service hours

announced.

Operators serious about profitability began modifying their cars to carry more passengers, and the motor bus was

born.

Nearly everywhere the activity was eventually stamped out by municipal or provincial legislation.

The universal technology of urban public transit in Canada in the 20th century. Every

community in the All-Time List of Canadian Transit Systems with local transit

service has been served by buses, except perhaps St. Stephen, New

Brunswick, and sufficient research will probably uncover local bus service there too.

Early known examples of motor bus transit include

Montréal – Saint-Lambert in 1904,

Calgary in 1907, and

Leamington in 1910.

The earliest existing transit [streetcar] company to implement a bus service was

Brantford in 1916.

The first appearance of motorized road transit in many Canadian cities was jitneys. Beginning on the west coast

in late 1914, private automobile owners began using their cars to pick up fare-paying passengers. In some cities

hundreds of cars were engaged in the trade, jitney associations were formed, routes established, and service hours

announced.

Operators serious about profitability began modifying their cars to carry more passengers, and the motor bus was

born.

Nearly everywhere the activity was eventually stamped out by municipal or provincial legislation.

1. Belleville, Ontario,

2. Brandon, Manitoba,

3. Centre Wellington, Ontario,

4. Corner Brook, Newfoundland & Labrador,

5. Creighton Mine, Ontario [Greater Sudbury],

6. Hamilton, Ontario,

7. Lockport, Manitoba,

8. London, Ontario,

9. Owen Sound, Ontario,

10. Montréal, Québec,

11. Ottawa, Ontario,

12. Saguenay, Québec,

13. St. John's, Newfoundland & Labrador,

14. St. Thomas, Ontario,

15. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan,

16. Toronto, Ontario,

17. Transcona, Manitoba,

18. Vancouver, British Columbia,

19. Vancouver – New Westminster, British Columbia,

20. Vernon, British Columbia,

21. Victoria, British Columbia,

22. Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Private automobiles organized as a commercial service to provide rides to the public reappeared in 2012 as Uber.

Several small communities, including a large number of rural localities

in some provinces, have in recent years implemented forms of public transit

service using techniques such as demand-responsive minibuses, shared-ride

taxis, and coordination of travellers with existing services (including

putting passengers on school buses and coordinating ride sharing, volunteer drivers, and carpooling).

Some of these approaches can also be found as part of services in larger communities where areas

or periods of low demand exist.

The All-Time List of Canadian Transit Systems tries to list those systems

that are open to everyone, and operate at least some scheduled service (even if

advanced booking is required). A few transit services whose sole

function is to put riders into others' vehicles are listed under

Québec Rural Paratransit Services.

- Bancroft, Ontario

- Brooks, Alberta

- Chapleau, Ontario

- Côte-de-Beaupré, Québec,

- D'Autray, Québec

- Deseronto, Ontario

- Devon, Alberta

- Fort Frances, Ontario

- Gaspésie, Québec

- rural Halifax

- Île d'Orleans, Québec

- Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Québec

- Laurentides - Pays-d'en-Haut, Québec

- Laurier-Station, Québec

- Madoc – Belleville, Ontario

- Northumberland [County], Ontario

- Nova Scotia Rural Paratransit Systems.

- Paris, Ontario

- Plessisville, Québec

- Port Hawkesbury, Nova Scotia

- Portneuf, Québec

- Rimouski, Québec,

- Saint-Pascal – La Pocatière, Québec

- Sainte-Marie / Saint-Isidore, Québec

- Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Québec

- Sept-Îles, Québec,

- Sorel-Tracy, Québec,

- Swift Current, Saskatchewan

- Thetford Mines, Québec

- Val-d'Or, Québec,

- Victoriaville, Québec,

- Wawa, Ontario

- Wetaskiwin, Alberta

- Yorkton, Saskatchewan

and more than a dozen small communities in

- Nunavut.

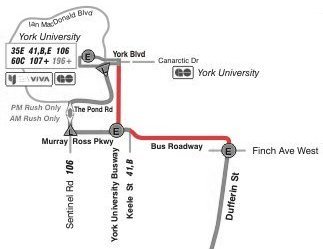

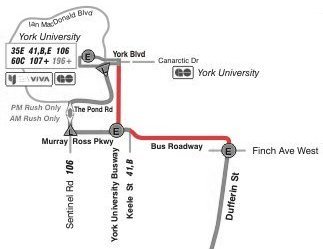

Application of private right-of-way using motor buses. The term “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transit) encompasses a wide range of technologies from conventional on-street/mixed traffic express bus service, to enhanced bus stops, bus-only lanes, signal pre-emptions, or

private road infrastructure with elaborate stations. In the context of the All-time List of Canadian Transit Systems

“motor bus busway” is intended to designate private right-of-way rapid bus service which includes stations.

The Toronto example listed below (and illustrated left) does not have stations, but is of substantial length.

Application of private right-of-way using motor buses. The term “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transit) encompasses a wide range of technologies from conventional on-street/mixed traffic express bus service, to enhanced bus stops, bus-only lanes, signal pre-emptions, or

private road infrastructure with elaborate stations. In the context of the All-time List of Canadian Transit Systems

“motor bus busway” is intended to designate private right-of-way rapid bus service which includes stations.

The Toronto example listed below (and illustrated left) does not have stations, but is of substantial length.

- Ottawa, Ontario Transitway (11 December 1983 - present)

- Toronto, Ontario York University busway (late 2009 - present)

- Winnipeg, Manitoba rt Southwest Transitway (08 April 2012 - present)

- York Region, Ontario VivaNext (18 August 2013 - present)

- Gatineau, Québec Rapibus (19 October 2013 - present)

- Mississauga, Ontario Transitway (17 November 2014 - present).

Animal drawn buses. (Commonly horses, possibly mules and probably not oxen in Canada.)

Since this transit technology was used in Canada almost

exclusively in the 19th Century, before the regulation or franchising of

over-the-road commerce, records of omnibus services are far from complete.

Animal drawn buses. (Commonly horses, possibly mules and probably not oxen in Canada.)

Since this transit technology was used in Canada almost

exclusively in the 19th Century, before the regulation or franchising of

over-the-road commerce, records of omnibus services are far from complete.

It was common practice in the animal street railway era to use omnibuses in spring after the snow melted

but before the ground was dry enough to operate the railway.

1. Beamsville, Ontario

2. Beauport, Québec,

3. Boischâtel, Québec,

4. Bowmanville [Durham Region], Ontario,

5. Brighton, Ontario,

6. Calgary, Alberta,

7. Cap-Rouge, Québec,

8. Charlesbourg, Québec,

9. Deseronto, Ontario,

10. Edmonton, Alberta,

11. Elora [Centre Wellington], Ontario,

12. Fort William [Thunder Bay], Ontario,

13. Goderich, Ontario,

14. Halifax, Nova Scotia,

15. Madoc, Ontario,

16. Midland, Ontario,

17. Milverton, Ontario,

18. Montmorency, Québec,

19. Montréal, Québec,

20. New Waterford, Nova Scotia,

21. Norwich, Ontario,

22. Oakville, Ontario,

23. Orillia, Ontario,

24. Orono [Durham Region], Ontario,

25. Ottawa, Ontario,

26. Owen Sound, Ontario,

27. Picton, Ontario,

28. Port Hope, Ontario,

29. Québec, Québec,

30. Ridgetown [Chatham–Kent], Ontario,

31. St. Catharines, Ontario,

32. Sainte-Foy, Québec,

33. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan,

34. Sillery, Québec,

35. Smiths Falls, Ontario,

36. Teeswater, Ontario,

37. Toronto, Ontario,

38. Victoria, British Columbia,

39. Walkerton, Ontario,

40. Welland, Ontario,

41. Windsor, Ontario,

42. Wingham, Ontario, and

43. Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Called “incline railways” almost everywhere in Canada.

Called “incline railways” almost everywhere in Canada.

- Bell Island, Newfoundland & Labrador (1913 - 1948)

- Edmonton, Alberta (1908 - circa 1913, 09 December 2017 - present)

- Hamilton, Ontario (1892 - 1936)

- Port Stanley, Ontario (1870 - 1966)

- Lévis, Québec (1904 - 1910)

- Montréal, Québec (1884 - 1918)

- Niagara Falls, Ontario (several, 1869 - present)

- Québec, Québec (circa 1880 - present) *

- Montmorency Falls, Québec (1901 - 1953)

* A British military incline railway at Québec (1823 - 1840s) reportedly also carried

the public.

Water barriers create a specific local transportation need, and ferries and

other marine transportation is the solution at places and times

where a bridge is not possible or practical. While a few services are obviously urban

transit (for example the seabus in Vancouver and the Dartmouth ferry), there

is a large grey area, especially historically, where boats play or played

a role in getting people from place to place in an urban area.

Water barriers create a specific local transportation need, and ferries and

other marine transportation is the solution at places and times

where a bridge is not possible or practical. While a few services are obviously urban

transit (for example the seabus in Vancouver and the Dartmouth ferry), there

is a large grey area, especially historically, where boats play or played

a role in getting people from place to place in an urban area.

- Halifax – Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

- Québec – Lévis, Québec

- Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario – Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan

- Sydney – North Sydney, Nova Scotia

- Toronto – Toronto Islands, Ontario

- Vancouver – North Vancouver, – West Vancouver, British Columbia

- Windsor, Ontario – Detroit, Michigan

Also belonging to this category are a number small-craft passenger boat services operated in various urban waterways. These include

Vancouver (False Creek),

Victoria (harbour),

and

Winnipeg (Red and Assiniboine Rivers),

Other ferry services are noted for

- Bell Island, Newfoundland and Labrador,

- L'Île-Dorval, Québec,

- Île-d'Entrée [Entry Island] (Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Québec),

- between Kelowna and Westbank,

- between Kingston and Wolfe Island,

- between Niagara-on-the-Lake and Toronto,

- between Sarnia, Ontario and Port Huron, Michigan,

- between Sorel-Tracy and Saint-Ignace-de-Loyola, Québec,

- between Winnipeg and St. Boniface, Manitoba,

- between Edmonton and Strathcona, Alberta,

- at Saint-Augustin, Québec

- between Southport [Stratford] and Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island,

- in the Saint John, New Brunswick area, and

- at Nanaimo, British Columbia.

- Asbestos & Danville Railway (electric freight railway)

- Edmonton Interurban Railway Company (suburban gascar railway)

- Expo Express (World's Fair heavy rail line)

- Hôpital Saint Jean de Dieu Railway (private electric freight railway)

- Lacombe and Blindman Valley Electric Railway Company (interurban gascar railway)

- Lake Louise Tramway (gascar tramway)

- Liverpool & Milton Tramway Company, Limited (steam dummy tramway)

- Mount McKay and Kakabeka Falls Railway Company (interurban gascar railway [eventually leased and electrified])

- Ontario Southern Railway (battery/electric monorail)

- Ontario West Shore (unopened interurban electric railway)

- Pacific Great Eastern Railway (suburban gascar railway)

- Roberval & Saguenay Railway Company (electric freight railway)

- Shawinigan Falls Terminal Railway Company (electric freight railway)

- Thurlow Railway Company (electric freight railway)

- Toronto Eastern Railway Company (unopened interurban electric railway)

- Train Léger de Charlevoix (local diesel passenger train)

- Western Power Company (BCER) (electric freight railway)

- Animal and gascar wilderness tramways

- Steam dummy railways operated at Windsor, Ontario,

Dundas, Ontario, and

Liverpool, Nova Scotia.

- Historically unproven information about street railway service exists for

East Broughton, Québec and

Fort Frances, Ontario.

Application of street railway-like technology to the transportation of passengers in

remote locations, most commonly horse-drawn portage railways.

See separate list.

In addition to the above listed heritage tramways

(Calgary,

Edmonton,

Nelson,

Vancouver, and

Whitehorse) there are street railway operating museums

at

- Milton, Ontario (the

Halton County Radial Railway),

- Delson, Québec (the

Canadian Railway Museum operated by the

Canadian Railroad Historical Association),

- Fort Edmonton Park, Edmonton, Alberta (the

Edmonton Radial Railway Society), and

- Surrey, British Columbia (the

Fraser Valley Heritage Railway).

A horse car line was operated at Heritage Park Historical Village, Calgary, Alberta (?-circa 1998).

The

Cornwall Electric Railway Society (1949-1952) preserved one Cornwall

streetcar and operated it over the then freight-only trackage

of the Cornwall Street Railway, Light

and Power Company, Limited. The group disbanded in 1952 and the

car was transferred back to the CSRL&P (Clegg & Lavalée 2007 pp. 57-61).

In the 1920's and 1930's three Canadian mainline railways,

Canadian National Railways,

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and

Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway

operated storage battery cars on several lines. In most of these

cases service never approached interurban levels, nor were they considered

separate from the railways' steam-hauled services. The largest user, the CNR,

had retired all its storage battery cars by 1942. (Photo: CN Images of Canada: Canada Science and Technology Museum)

In the 1920's and 1930's three Canadian mainline railways,

Canadian National Railways,

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and

Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway

operated storage battery cars on several lines. In most of these

cases service never approached interurban levels, nor were they considered

separate from the railways' steam-hauled services. The largest user, the CNR,

had retired all its storage battery cars by 1942. (Photo: CN Images of Canada: Canada Science and Technology Museum)

Canadian National Railways (16 May 1921 - circa 1942)

- Trenton – Belleville, Ontario [22km/13.8mi] 16 May 1921 - 19 June 1921 (trial),

- Campbellton – Bathhurst, New Brunswick [100km/63mi] [101km/62.9mi] 1921 - 1922,

- Campbellton, New Brunswick – Matapedia, Québec [21km/13mi],

- Toronto – Beaverton, Ontario [103km/64.2mi] September 1922 - ?,

- Toronto – Weston, Ontario [13.4km/8.4mi] 1923 - ?,

- Toronto – Oakville, Ontario [34km/21.3mi] 1924 - ?,

- Montréal – Saint-Eustache, Québec [27km/17mi] 1924 - ?,

- Montréal – Rawdon, Québec [66km/41.4mi] 1924 - ?,

- Montréal – Waterloo, Québec [107.5km/67.2mi] 1924 - ?,

- Ottawa – Pembroke, Ontario [143km/89.5mi] 1924 - ?,

- Halifax – Windsor Junction, Nova Scotia [25.6km/16mi],

- Lunenburg – Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia [11.2km/7mi] 1937? - 1961?,

- Fredericton – Centreville, New Brunswick [141.6km/88.5mi],

- Sainte-Rosalie – Nicolet, Québec [96km/60mi],

- Fort Erie, Ontario – Black Rock, New York (over International Bridge),

- Winnipeg – Transcona, Manitoba [14.4km/9mi],

Canadian Pacific Railway Company (? - ?)

- Galt – Hamilton, Ontario [55km/34.4mi], and

Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (? - ?)

- Swastika – Kirkland Lake, Ontario [9km/5.6mi].

(Martin)

The Ontario Southern Railway was also operated by storage battery.

Martin also lists the Toronto – Guelph line of the interurban Toronto Suburban Railway as receiving battery cars in 1924, but

other traction historians disagree (Martin, RFC).

Copyright ©1989-2023 David A. Wyatt. All Rights Reserved.

Return to All-Time List of Canadian Transit Systems

The author is always interested in comments, corrections and further information. Please email to: dawwpg@shaw.ca

This page last modified: Wednesday, 30-Aug-2023 20:45:14 CDT

![]() 1. Brantford,

2. Chatham,

3-4. Galt [Cambridge] – Kitchener,

5. Temiskaming Shores,

6-9. Hamilton,

10. Hull [Gatineau],

11-12. London,

13. Montréal,

14. New Glasgow,

15. Niagara Falls,

16. Québec,

17. St. Catharines – Niagara Falls,

18. Sydney,

19. Thunder Bay‡,

20-21. Toronto,

22. Vancouver,

23. Victoria,

24-25. Windsor,

26. Winnipeg, and

26. Woodstock.

1. Brantford,

2. Chatham,

3-4. Galt [Cambridge] – Kitchener,

5. Temiskaming Shores,

6-9. Hamilton,

10. Hull [Gatineau],

11-12. London,

13. Montréal,

14. New Glasgow,

15. Niagara Falls,

16. Québec,

17. St. Catharines – Niagara Falls,

18. Sydney,

19. Thunder Bay‡,

20-21. Toronto,

22. Vancouver,

23. Victoria,

24-25. Windsor,

26. Winnipeg, and

26. Woodstock.

![]() 1. Belleville,

2. Brandon,

3. Brantford,

4. Calgary,

5. Cornwall,

6. Edmonton,

7. Fort William,

8. Glace Bay,

9. Guelph,

10. Halifax,

11. Hamilton,

12. Hull [Gatineau],

13. Kingston,

14. Kitchener – Waterloo,

15. Lethbridge,

16. Lévis,

17. London,

18. Moncton,

19. Montréal,

20. Moose Jaw,

21. Nelson,

22. New Westminster,

23. Niagara Falls,

24. North Sydney – Sydney Mines,

25. North Vancouver,

26. Oshawa,

27. Ottawa,

28. Peterborough,

29. Port Arthur,

30. Québec,

31. Regina,

32. St. Catharines,

33. Saint John,

34. St. John's,

35. St. Stephen,

36. St. Thomas,

37. Sarnia,

38. Saskatoon,

39. Sault Ste. Marie,

40. Sherbrooke,

41. Sudbury,

42. Sydney,

43. Toronto,

44. Trois-Rivières,

45. Vancouver,

46. Victoria,

47. Welland,

48. Windsor,

49. Winnipeg, and

50. Yarmouth.

1. Belleville,

2. Brandon,

3. Brantford,

4. Calgary,

5. Cornwall,

6. Edmonton,

7. Fort William,

8. Glace Bay,

9. Guelph,

10. Halifax,

11. Hamilton,

12. Hull [Gatineau],

13. Kingston,

14. Kitchener – Waterloo,

15. Lethbridge,

16. Lévis,

17. London,

18. Moncton,

19. Montréal,

20. Moose Jaw,

21. Nelson,

22. New Westminster,

23. Niagara Falls,

24. North Sydney – Sydney Mines,

25. North Vancouver,

26. Oshawa,

27. Ottawa,

28. Peterborough,

29. Port Arthur,

30. Québec,

31. Regina,

32. St. Catharines,

33. Saint John,

34. St. John's,

35. St. Stephen,

36. St. Thomas,

37. Sarnia,

38. Saskatoon,

39. Sault Ste. Marie,

40. Sherbrooke,

41. Sudbury,

42. Sydney,

43. Toronto,

44. Trois-Rivières,

45. Vancouver,

46. Victoria,

47. Welland,

48. Windsor,

49. Winnipeg, and

50. Yarmouth.

![]() In most

cases the use of animal power on street railways in Canada included the use

of sleighs in winter. In some cities omnibuses were routinely used to

provide service during the Spring thaw.

In most

cases the use of animal power on street railways in Canada included the use

of sleighs in winter. In some cities omnibuses were routinely used to

provide service during the Spring thaw.

Application of private right-of-way using motor buses. The term “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transit) encompasses a wide range of technologies from conventional on-street/mixed traffic express bus service, to enhanced bus stops, bus-only lanes, signal pre-emptions, or

private road infrastructure with elaborate stations. In the context of the All-time List of Canadian Transit Systems

“motor bus busway” is intended to designate private right-of-way rapid bus service which includes stations.

The Toronto example listed below (and illustrated left) does not have stations, but is of substantial length.

Application of private right-of-way using motor buses. The term “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transit) encompasses a wide range of technologies from conventional on-street/mixed traffic express bus service, to enhanced bus stops, bus-only lanes, signal pre-emptions, or

private road infrastructure with elaborate stations. In the context of the All-time List of Canadian Transit Systems

“motor bus busway” is intended to designate private right-of-way rapid bus service which includes stations.

The Toronto example listed below (and illustrated left) does not have stations, but is of substantial length.

In the 1920's and 1930's three Canadian mainline railways,

Canadian National Railways,

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and

Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway

operated storage battery cars on several lines. In most of these

cases service never approached interurban levels, nor were they considered

separate from the railways' steam-hauled services. The largest user, the CNR,

had retired all its storage battery cars by 1942. (Photo: CN Images of Canada: Canada Science and Technology Museum)

In the 1920's and 1930's three Canadian mainline railways,

Canadian National Railways,

Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and

Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway

operated storage battery cars on several lines. In most of these

cases service never approached interurban levels, nor were they considered

separate from the railways' steam-hauled services. The largest user, the CNR,

had retired all its storage battery cars by 1942. (Photo: CN Images of Canada: Canada Science and Technology Museum)